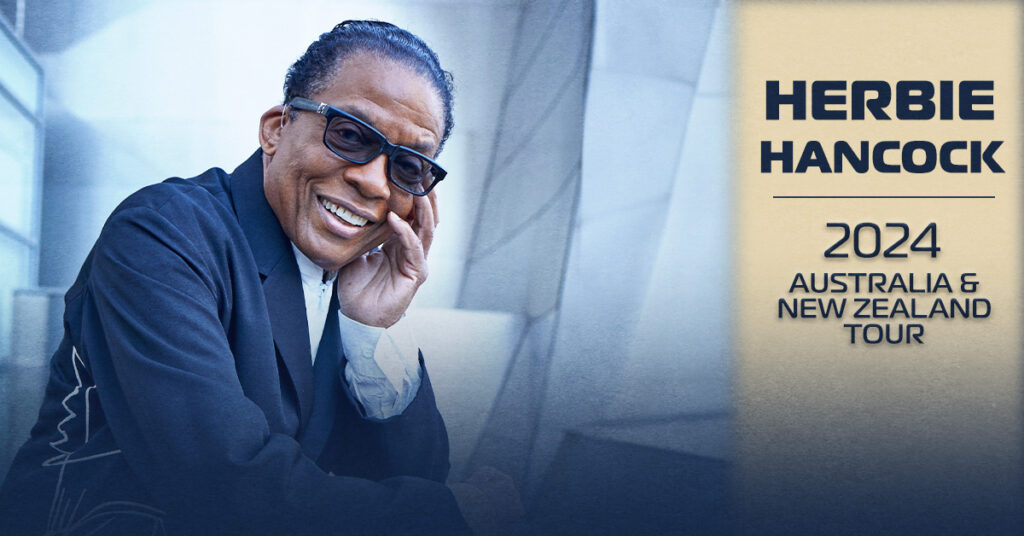

Herbie Hancock

Festival Theatre.

October 20.

It was (almost) fifty years ago today that Herbie Hancock got the band to play : Head Hunters. The million-seller jazz fusion break-out of 1974. It was a much acclaimed album along with the first releases from Weather Report and Mahavishnu Orchestra and indicative of Hancock’s versatility and keen sense of the way the wind was blowing.

A classical prodigy, at the age of eleven he played a Mozart piano concerto with the Chicago Symphony. But listening to records by piano greats such as George Shearing, Errol Garner, Bill Evans and Oscar Peterson brought him ever closer to jazz. At 21 he was working with Donald Byrd and Coleman Hawkins. Then, in 1962, his Blue Note solo album Takin’Off took off with the signature hit “Watermelon Man”.

The world was listening – including Miles Davis who, in 1963 hired Hancock for his celebrated quintet until 1968. It was there, in the company of Ron Carter, Tony Williams and Wayne Shorter that he cemented his early promise. Hancock featured on such classic pressings as Miles Smiles, Sorceror and Nefertiti.

When Miles in the Sky went electric – Carter on bass, Hancock on piano – it was the beginning of the fusion adventure which incorporated the burgeoning funk and rock sounds of the late Sixties with the rapid evolution of keyboard technology – Fender Rhodes, Arp Odyssey, the Hohner clavinet and much more. Hancock stayed with Davis as he forged into places many disdained to tread. He played on the Jack Johnson and On the Corner sessions which sound even more amazing than they did fifty-five years ago.

Hancock’s other projects took a different turn and are among his most enduring. Mwandishi released in 1971, followed by Crossings a year later featured a quintet of the highest order. Taking on Swahili names in acknowledgement of the Back to Africa project in American Black politics at that time, the band – including trumpeter Eddie Henderson, reedman Bennie Maupin, the ethereal trombonist Julian Priester and a rhythm section comprising Billy Hart and Buster Williams – created a textured, fluid sound with almost disconcerting time changes of considerable subtlety and beauty. It is still one of my favourite periods of Hancock’s extraordinary career.

Onstage at the Festival Centre Herbie Hancock is still in complete command of his musical destiny. At 83, after 62 years as an undisputed leader in jazz he radiates a delight in his calling and pleasure in his continuing invention. Dressed in a long black frock coat, tinted specs, his hair crimped and gleaming, he is as stylish as ever, princely even. As the band assembles he takes up the microphone to introduce the proceedings.

Always affable and urbane Hancock immediately acknowledges the band- “These guys are so creative, as you will hear.” And – in a good way – he also flatters the audience . We are not only going to be a fantastic audience, we are central to the dynamic of the performance. They are not a quintet, he observes, the presence of the audience makes them a sextet- “You are part of what makes us play”.

Looking down at his setlist he introduces the “Overture” aka “Prehistoric Predator” – an obscure reference he quickly discards to say it will be “bits and pieces from the past fifty years or so.” The band proceeds to unleash a farrago of sounds – rushing surges, whistles, whoops, squelch accents, and then Hancock’s familiar clusters and chords on the piano.

It gathers strength and momentum – and volume. Trumpeter Terence Blanchard provides an assured, tensile lead (as he will all evening) James Genus’s bass looms low and ominously, Lionel Loucke’s heavily processed guitar adds fills and ripples while Jaylen Petinaud guides, bob and weaves with his immaculate drumming. It is a thrilling combination and it brings the reveries and questioning dissonances of the Mwandishi and Crossings period recordings vividly to life. Those extended explorations such as “Wandering Spirit Song” and Sleeping Giant” are evoked if not directly quoted.

Hancock’s acoustic piano playing (on a Venetian Fazioli which he stipulated for all concerts in this Australian tour) is dexterous and hypnotic before he swivels to his favoured Korg Kronos keyboard for the hard-edged funk fanfare opening to “Chameleon”, centrepiece from the Head Hunters album and leitmotif for much of the evening. The band goes full throttle and the precision is delectable.

The setlist consists of just six items- which are pretty much unvarying in the setlists for the whole tour. Hancock pays understated but heartfelt tribute to “my best friend,” the late Wayne Shorter, with a reading of “Footprints” composed by Shorter for his 1967 album Adam’s Apple.

Opening with Genus’s cavernous bass, Loueke vamping on guitar and Hancock’s decorative piano, the fifteen minute rendition is led by Blanchard’s superb musicianship. That the central melody is played on a trumpet and not saxophone, as Shorter would have done, is both audacious and revelatory.

Hancock’s solo is archetypically playful and melodic, then Loueke’s guitar deals in with a swing rhythm, while Genus thrums bass and Petinaud’s drumming is crisp and emphatic. All of this, though, is to serve Blanchard’s majestic trumpet. Sometimes it sounds like Jon Hassell, others Dizzy Gillespie – and often, the Picasso of jazz, Miles Davis, master of timbre and mood. Composer of more than 80 film scores and two operas performed at the New York Met, Terence Blanchard, with his bleached cropped hair, conspicuous bling, and iridescent leather britches, is a star to rival Hancock himself.

“Actual Proof “ from the 1974 Thrust album is the next excursion. Beginning with drum agitations from Petinaud and strutting and fretting from Loueke’s ever-morphing guitar, Blanchard then continues with what might be the melody line before Herbie takes charge with cascades of frenetic funk-bop – swivelling from Korg to piano as the band splendidly threads together once more. James Genus takes another intrepid solo before getting into lock-step with Petinaud, who delivers a solo voyage of his own to conclude.

“It is not easy playing with these guys,” Hancock exclaims after this actual proof of the band’s prowess. Then he grins with pride- “But it’s not that hard either.” Introducing the players he says of Jaylen Petinaud –“he’s young enough to be my grandson” adding that the next generation of jazz is in safe hands.

James Genus, we are reminded, is resident bassist with Saturday Night Live and attention turns to Lionel Loueke. “Have you ever heard anyone play guitar like that ? “ Hancock exudes. From Benin, Loueke brings an extraordinary range of effects and rhythms, pressing pedals which turn his instrument into a West African kora and other traditional sounds.

Along with his pioneering synth and clavinet work Herbie Hancock was an early adopter of the vocoder, a gizmo favoured by Kraftwerk, ELO, Daft Punk and numerous others that turns the human voice into data signals which compress, encrypt and transform range and sounds into electronica. After some light-hearted demos of its wizardry, Hancock performs (with vocal assist from Loueke, and a meditative solo from Genus) his heartfelt hymn to peace and harmony – “We Are All One Family”.

The program definitely favours the fifty year vintage repertoire with “Three-in-one” – a medley mashup of “Hang Up Your Hang Ups”, “Rockit” and “Spider”. For “Rockit” Hancock takes up his other early prototype instrument , the Keytar – a keyboard designed to be slung over the shoulder like a guitar with fret-like fingering as well as piano keys. It is not the neon sizzling “Rockit” sound of the famous Top Ten hit and Grammy winner, rather the band finds a more restrained and nimble funk vibe, assisted by Blanchard on keyboards. And this brilliant new variation is just as catchy and ear-wormy as ever.

And speaking of ear-worms, “Chameleon” comes back as the closer . Those opening fanfares, again from the keytar. Hancock mooches, like Chuck Berry, closer to the rhythm section, duetting with the bass and urging on Petinaud’s flawless drum rhythms. Loucke dials up more unguitar-like sounds and also pairs with Hancock, generating a groove like two aliens introducing themselves to each other in the intergalactic language of Electrofunk, Herbie doing a little bouncy Moon shuffle of sheer elation.

Hancock chose his song well. He is a musical Chameleon who has adapted, shapeshifted and morphed, remade and renewed himself many times in his stellar career. But, at the same time, his style and signatures have never really changed.

Who was it who said – “We shall not cease from exploration/ And the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time.” ?

murraybramwell.com